Educator and anti-racism activist Jane Elliott, known for her "Blue eyes/Brown eyes" exercise, joins us to talk about the role white women play in education and upholding racist systems. She also shares how to be a true ally in the fight to for a more equitable future.

"I hope that they will understand that they have the power to make a difference, that one person can make a difference, that one person can change the world. If they see something that needs to be changed, they need to take the responsibility for changing it."

Lisa Hollenbach: We at Brightbeam have set out to tell the story of how white women, as mothers and as teachers, have historically used their positions of power to perpetuate systems of oppression, and how that history remains alive and active today. Part of that story celebrates the outliers in history, the white women who have acted as accomplices, who bucked that system and worked to provide a just education to black and brown young people, also to build empathy in white children. So that we might build a better future together, sometimes at significant personal costs. You, Jane, clearly are one of the accomplices. So I'd like to take you back to that day in April, 1968, when you first walked into that classroom and began your famous brown eyes, blue eyes experiment with your third grade class.

We know that white women dominate the teaching profession, and we also know that as a rule, many of the white women in our schools continue to do harm and they're not standing up and speaking out against the racism and the inequality that's happening in classrooms today. And I'll tell you why. Wait a minute.

Jane Elliot: I'll tell you why. They don't speak out. Speak out. Okay. They wanna keep their jobs. Exactly. And it's more dangerous now to stand up and say, look, we're all one race in this classroom and we're all going to treat one another. Look members of the same race you are all my 30th, two 50th cousins. Now, if your parents don't appreciate that, that's their problem. But in this room, this is the way you're going to be treated every. person in this room is going to be treated, we are going to use the three R's in this room, and that's not reading, writing, and arithmetic, since only one of those words begins with R. So boys and girls, in this classroom, we're going to learn the three R's of Rights, Respect, and Responsibility.

I am going to hold you responsible for respecting the rights of every person in this building. Not just in the building, but on the playground, on the bus, on the street when you see them, downtown when you go to see Santa Claus, and get in line. Observe rights, respect, and responsibility in your communications with other people in the future. After you leave this classroom, if I see you on the street, and I see you not respecting somebody else's rights, I will step up and say, Didn't you learn enough in third grade? How would you like to come back and repeat the class? Because obviously you forgot what I tried to teach you.

It's time for us to start teaching the truth instead of the lie. There's only one race of people on the face of the earth. There are lots of different color groups, lots of different national groups, lots of different... Gender groups and sexual orientation groups, but they're all members of the same damned race. And if we don't stop what we're doing, we are going to be damned because of our desire to promote the idea of a white race. Kids have to know and adults have to know that only from 15 to 18% of the human beings living on the face of the earth are classified as white. Did you know that?

Lisa: I'll tell you the other reason I know that is because I've watched your interviews.

Jane: Okay, so I'm repeating myself and people say to me I've heard before I've heard before I've heard before but if you have an object or something to sell if you have a product to sell the people Watch the television or wherever they're advertising it. Have to hear that advertisement list at least four times before they'll buy the product.

So I will say at least a thousand times before, no, more than that before I die. Because I expect to live for another 10 years and that's a threat, I know. But that's the way it's going to be. Because I'm not going to die until we have gotten over the idea. More than one race. I'm going to say that over and over and over until people get it into their heads that that's the truth.

And I'm a Christian, so I believe ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall set ye free. Now, I wouldn't be a Christian if it hadn't been for Jews. People have, who are... Marching against, who are saying, Jews will not replace us, these silly proud boys, what they have forgotten is there wouldn't be Christians, or Muslims, or Baha'is, if it weren't for the Jewish people.

The first five books of the Bible, of the Old Testament, came out of the Torah. Evidently, these ignorant people don't know that, but you see, you're talking about education. I'm an educator. We have these kids, all day, every day, for at least eight hours a day, six to eight hours a day, for 12 years of their lives. We can take any child, any color from any part of the world, and we can educate them in such a way that they will become prejudiced against anyone who doesn't look like them. Why don't we do the same thing with kindness, love, understanding, empathy, and treating people as equals? I have never been able to understand that. It makes no sense to me. It's as though people want to keep the hate alive, they want to keep racism alive.

Lisa: Well, they do. I think it's not just as though. I think it's because it's a system of power and if we teach our children, and I agree with you, I think it starts in those classrooms, if we teach them something different, if we teach them to love, if we teach them to care, if we teach them to empathize, then that system of power and control starts to lose its grip.

Jane: That's right. That's right. That's what we have to do. We have to get teachers to be willing to teach the truth. We have to help teachers be willing to teach the truth. Now we have to tell parents, if you have a problem with your child being taught by a teacher who's trying to teach them the truth, you need to look in the mirror and say, what's the matter with me that I don't want my child to know the truth? But there are too many parents who want their children to be prejudiced, they want their children to hate, they want their children to be members of a particular group, and they're proud of it. And that's disgusting.

Lisa: Yeah, it is. It's very frustrating and heartbreaking. So I wanna take you back to that classroom because I know that I saw you talk with Trevor Noah about your work, and you talked about the idea that you wouldn't do that experiment today. You felt that it was too risky, which I completely understand. But you talk about that moment in 1968, where you decided to separate the kids based on their eye color and you said, "I think I can do this with third graders."

And I have to ask the question, what was the spark that lit that flame? What led you to make that decision that morning?

Jane: Ignorance led me to make that decision. I was ignorant of the power of teaching, the power of prejudice, the power of discrimination. I was a naive young woman who had been raised in a very religious, very white, very righteous family in eastern South Dakota, one of the whitest states in the Union. I'd been raised with the idea that the white people were the superior people. I'd been raised with the idea that I was very fortunate to have been born into the right family and the right religion, the right color, the right nationality, and the right... We believed the right everything.

And so I came to this job in Riceville, Iowa, in 1968, believing all of that stuff. And that's a very dangerous attitude to have when you're an educator, when you're working with little children. So I was... I was raised in this society. I was racist and I didn't even know it. I didn't even know it. And one day, after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed, I looked at my all-white classroom, and I thought, I need to do something about racism.

I need to make these children understand how it feels to be judged on the basis of something over which they have no control, and I had no idea what I was going to do. And I was sitting there, in my apartment, the only place I had any privacy, and I looked down and I saw a bottle of blue food coloring and I thought, what if I separate my kids on the basis of the color of their eyes? What will that teach them?

And so I decided to do that. I made a couple of phone calls, talked to a friend in the school system, who said, you're gonna get fired if you do that. And I thought, well, maybe I won't get fired. So I did it. I separated my kids on the basis of the color of their eyes. It was the most terrifying day of my life.

Lisa: Yeah, I bet. And you mentioned the risk and the fear of getting fired, but I can't help but think about the risk and the fear that those third graders experienced that day. I mean, they had no idea what was coming, and suddenly their whole world was turned upside down based on the color of their eyes. Can you talk about what that experience was like for them and how they reacted?

Jane: It was the first day in which they were not treated as individuals, as the people that they were, as the human beings that they were. It was the first day in which they were treated on the basis of an artificial criteria that had nothing to do with their humanity, with their intelligence, with their ability, with their potential. And that was a shock to them.

And it was a shock to the kids who were on the top, the brown-eyed kids who were now on the top. Because as the morning wore on, they got more and more aggressive, more and more disrespectful, more and more superior, more and more intolerant of those who had been on top the day before. So it was not easy for any of the kids. And it was very difficult for me because I'm standing there thinking, am I ruining these kids? Have I ruined these children's lives? Have I ruined their personalities? Have I changed them?

Lisa: So as you went through that day, and you saw these changes happening, did you ever doubt your decision? Did you ever think, maybe I made a mistake here?

Jane: No. Because I'm not a quitter. I was not going to allow that situation to happen in my classroom without teaching them the lesson that I had set out to teach. And I wasn't going to stop until they had learned that lesson.

I had to let them know that, this is not the way to treat other people. You do not treat other people in this manner. You do not discriminate against other people. You do not make judgments about other people on the basis of physical characteristics over which they have no control. And I couldn't stop until I had taught that lesson.

Lisa: And so, after that first day, when you had taught that lesson, what did you see in your students? How did they react after that initial experiment?

Jane: The first day, after the first part of the lesson, the second half of the day, they went back to treating one another as human beings. And we talked about what had happened during the day, and what they had learned. And they talked about the fact that, when we were doing that, when we were treating other people unfairly, they felt like they were bigger, they felt like they were more powerful, they felt like they were superior. They felt like they were smarter. And that they didn't have to listen to anyone else.

And then the second half of the day, when we treated everyone the same, they said, "But then we realized that we were not as smart as we thought we were, we were not as nice as we thought we were. We were not as big as we thought we were, and we didn't feel as good about ourselves as we felt before." So they had learned that the way they were being treated was the way they were feeling about themselves, which was very, very important.

Lisa: It's such a powerful lesson, and it really highlights how our perceptions and our treatment of others can affect not only them but also ourselves. So, after that initial experiment, you continued to do this for a second day, where you switched the roles, and the blue-eyed children became the superior group. What was the purpose of that second day?

Jane: The purpose of the second day was to help the brown-eyed children understand how it felt to be treated as a minority, to be treated as if they were inferior, to be treated as if they were not as capable as the others. And that lesson, if they had any doubt about the lesson on the first day, they learned it on the second day.

And it was very important for the brown-eyed children to learn that lesson because I knew that they would be the white people of the future, that they would be the people in power. And I didn't want them to grow up to be the kinds of people who believed that they were superior to others simply because of the color of their skin.

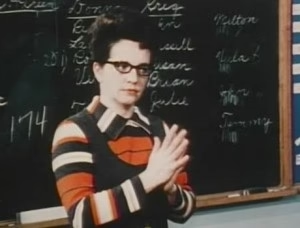

Jane Elliot in class, 1968.

Jane Elliot in class, 1968.

So the second day was very important for them to learn that lesson, and they learned it. They learned it very well. And the first day, the brown-eyed kids didn't learn the lesson as well as I had hoped they would. They learned it well, but not as well as I had hoped. And that was my fault. I should have debriefed them at the end of the day, and I didn't.

So the next year, when I did it again, with a different group of kids, at the end of the day, I told them that we were going to treat everyone the same the next day, but I wanted them to think about what had happened the day before. And I wanted them to write about it, to write about how they felt, to write about what they had learned.

And when they came in the next day, I asked them if they wanted to read what they had written. And they all did. And when they read what they had written, the lesson was very, very clear to them. And they all said, "We don't want to treat anyone the way we treated people yesterday."

Lisa: It's amazing how reflection and self-awareness can really drive home those lessons and make them stick. So you continued this exercise in the years that followed, and it gained national attention. What was the response from parents, the community, and even other educators when they learned about what you were doing in your classroom?

Jane: The parents were not happy with me. Many of the parents were very unhappy with me. They believed that what I was doing was wrong. They believed that I was brainwashing their children. They believed that I was teaching their children to hate themselves because they were white. And they didn't want their children to be taught to hate themselves.

The school board was not happy with me. The superintendent of schools was not happy with me. Many of the teachers were not happy with me because I was doing something that was not being done in other schools, and it made them look bad. It made them look like they weren't doing their jobs. It made them look like they weren't doing what they should be doing.

The community was not happy with me. I was called a communist, I was called a n****r lover, I was called all kinds of names. I got hate mail and death threats. I got bomb threats. I got calls in the middle of the night, telling me that they were gonna kill me if I didn't stop what I was doing. So the response was not good.

Lisa: That's incredibly difficult to hear, but it also shows just how deeply ingrained these prejudices and biases were in the community at that time. And it must have been incredibly challenging to continue doing this work in the face of such opposition.

Jane: It was very challenging, but I couldn't stop. I couldn't stop because I knew that I was right. I knew that I was doing the right thing. I knew that I was teaching a lesson that had to be taught. And I knew that I was doing what I had to do. And I knew that it was more important to do what I had to do than it was to listen to those people who were trying to stop me.

Lisa: And that determination and that conviction really shines through in your story. So, as time went on, did you see any changes in the attitudes or perceptions of the parents, the community, or the students themselves as a result of your work?

Jane: The students changed right away. The kids that I taught changed right away. And I knew that because the next year, when I would do it again, they would... They never treated one another the way they had treated one another the first time. And they had changed.

The parents, on the other hand, many of them never changed. Many of them continued to be very angry with me, and they continued to oppose me. And I was... At one point, after a particularly difficult encounter with a parent, I was in tears in the teachers' lounge. And the teacher who was in charge of the teachers' lounge said to me, "Jane, don't you ever let them see you cry. If you let them see you cry, they'll know they've won. You keep your tears for the people who are gonna benefit from them."

And that was good advice, and I took it to heart. And I never let them see me cry after that. But it was not easy. It was not easy.

Lisa: I can only imagine how challenging that must have been. But it's clear that your work had a profound impact on the students you taught, and it continues to inspire people today. So, what do you hope people take away from your story and your work, especially in the context of today's ongoing struggles with racism and prejudice?

Jane: I hope that people will understand that racism is a learned behavior. That nobody is born a racist. That we are taught to be racists by the society in which we live, and that we can unlearn that behavior. We can stop being racists. We can stop being prejudiced. We can treat one another as equals. We can treat one another with respect. We can treat one another with kindness and empathy.

I hope that people will understand that we are all human beings. We are all part of the same race, the human race. And that we are all part of the same family, the family of humanity. And that we need to treat one another as family members. And I hope that they will understand that it's important to stand up and speak out when they see someone being mistreated, when they see someone being discriminated against, when they see someone being treated unfairly, to stand up and say, "This is not right. This is not what we should be doing."

And I hope that they will understand that they have the power to make a difference, that one person can make a difference, that one person can change the world. And if they see something that needs to be changed, they need to take the responsibility for changing it. And that's what I hope they take away from my story.

Subscribe to our Youtube channel and watch part two of the interview.

Former Head of AI for Meta, Jerome Pesenti is the founder of Sizzle, an AI-powered "learning...

Heather Harding, Ed.D., Executive Director of the Campaign for Our Shared Future, joined Chris and...

In the ongoing battle of education's culture wars, Chris and Sharif emerge as beacons of clarity,...

The story you tell yourself about your own math ability tends to become true. This isn’t some Oprah aphorism about attracting what you want from the universe. Well, I guess it kind of is, but...

If you have a child with disabilities, you’re not alone: According to the latest data, over 7 million American schoolchildren — 14% of all students ages 3-21 — are classified as eligible for special...

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

Your donations support the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.