Written by Stephan Maldonado | Feb 16, 2018 5:00:00 AM

I was in my sophomore year at an all-boys’ Catholic high school in the Bronx the first time I saw a school administrator lay hands on a student. We had a very strict dress code that included being clean-shaven, and my classmate had refused to go to the nurse’s office to shave his mustache. When our teacher was unable to make the student leave, she called for our dean of discipline—a man whose job it was to dole out detentions and handle unruly students. This kid was

not unruly from my standpoint, but when the dean got involved, words were exchanged and [pullquote position="right"]my classmate ended up pinned against the wall with the dean shouting in his face.[/pullquote] Such occurrences were common throughout my high school experience. While they were always shocking, it wasn’t until years later (as I began writing about issues in education), that I understood them to be part of a far-reaching problem: a systematic-yet-unspoken policy of excessively punishing certain students for minor infractions. More alarming is that as troubling as my school’s practices were, many students face far harsher realities. Take Niya Kenny, a Spring Valley High School senior in Columbia, South Carolina. Niya reacted as many teenagers might have the day she witnessed the

violent arrest of a classmate: She pulled out her cell phone and began recording. The incident occurred in 2015, during math class, when Niya’s classmate refused to give up her cell phone. Ben Fields, a school-based police officer, was called to escort the student from the classroom. After a brief altercation, Fields grabbed the student’s desk, flipped it over and dragged her across the floor. Horrified, Niya started

recording the arrest, repeatedly asking Fields why he was doing this to someone who hadn’t done anything. Niya was arrested immediately following her classmate’s arrest. Both students are African-American, and both were charged with “disturbing a school” and taken to a detention center. Their arrests drew widespread attention to an ongoing conversation about racial tensions and school-related arrests in America. Their ethnicities may be an important detail. An in-depth investigation by

Education Week found that, on the national level, African-American male students are three times more likely to be arrested than White male students in schools that have a police officer presence. [pullquote]African-American female students are 1.5 times more likely to be arrested than White male students.[/pullquote] My school did not have a police presence, yet students could still be forcibly removed from classrooms. Imagine what that would have looked like if we

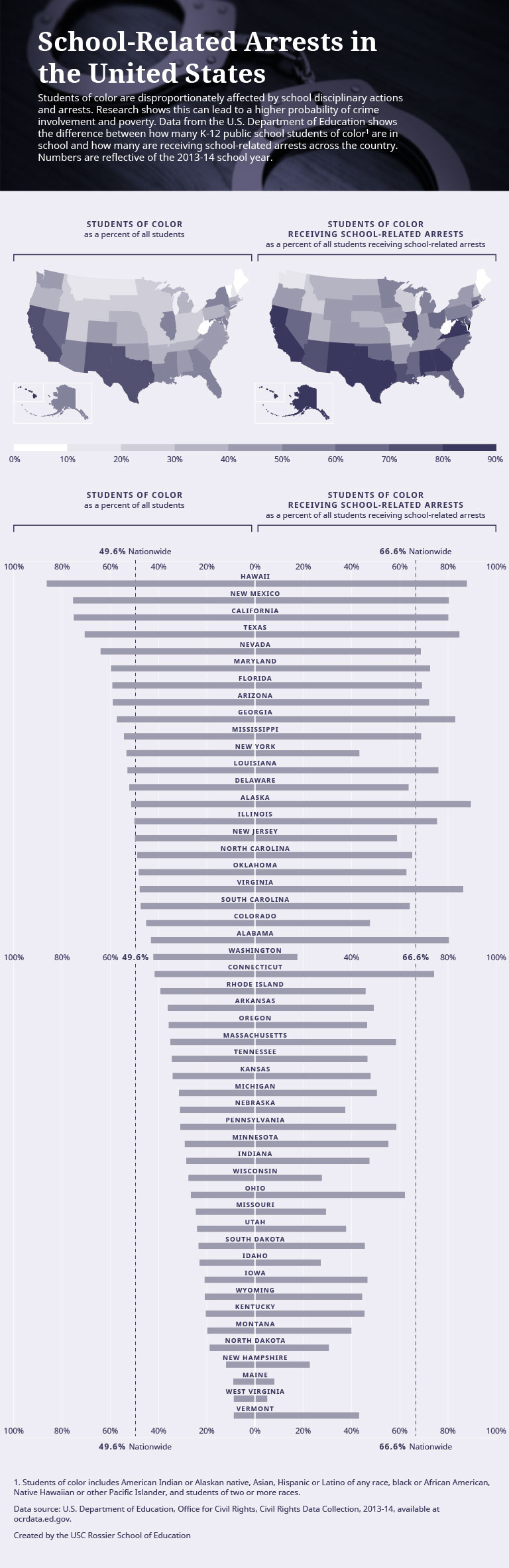

did have a police officer on call? In New York state, where I went to school, African-American students represent 17.9 percent of all students enrolled in schools, but they make up for

27.5 percent of student arrests. In contrast, African-Americans make up 35 percent of student enrollment in South Carolina schools, where Niya went, yet they comprise

53.7 percent of all student arrests. The Education Week investigation, using data collected by the U.S. Department of Education for the

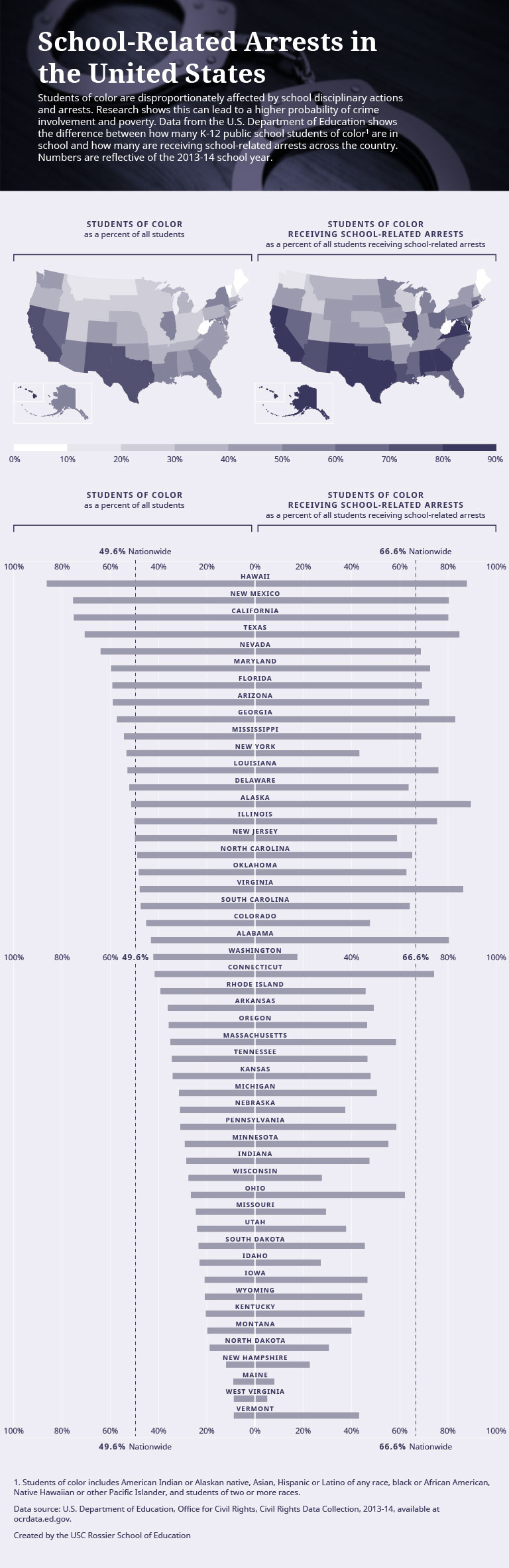

2013-2014 school year, finds that African-American students face the highest levels of arrests. The trend continues for students of other ethnic minorities, too. What do these numbers say about the current state of race relations in our public schools? What are the lasting repercussions of such strict disciplinary measures taken primarily against students of color? And what can concerned teachers do? (Besides becoming the administration themselves—which isn’t a bad idea for those especially committed to organizational change.)

See For Yourself

- Recognize if you’re part of the problem. We all have blind spots.

- Advocate for more diversity in teaching. And administration too.

- Have uncomfortable conversations. Your kids need to hear from you that the idealized versions of equality issues aren’t exactly reality yet.

- Educate yourself and become the establishment. If you can’t beat ’em… join them and make organizational change happen on your own terms. Especially if you look like your students.