Jul 24, 2019 12:00:00 AM

by Debbie Meyer

When our son was born, my husband and I knew a lot about how to prepare him to be a reader. We knew how to speak parentese—the exaggerated, higher-pitched language that helps babies and toddlers learn words. We read storybooks daily and read the New York Times to him, too. We listened to radio news rather than watching TV news, because, on the radio, events are described in more depth with a richer vocabulary.

Since we live in New York City, we don’t have to drive. When we walked, we talked about what we saw—pink flowers, garbage trucks, tall buildings, squirrels, dogs, large and small. When we rode the bus and subway, we read books. We didn’t stay tied to our Blackberry phones or wear headphones. We walked and talked our way through art, history and science museums.

While we were his primary guides, our son learned language from a community, too. He learned language by speaking with our neighbors and extended family, too. He learned from our full-time babysitter as well as from preschool. As early as pre-K, we began to hear from his teachers, “Your son has so much background knowledge; it is a joy to have him in class.” It was something we would hear from every teacher through eighth grade.

But, even in pre-K, our son could not identify rhymes. [pullquote position="right"]Although he could easily memorize entire books, he had little phonemic awareness.[/pullquote] He understood the arc of story, and with more complicated books, foreshadowing. Vocabulary, background knowledge and comprehension were not his problems.

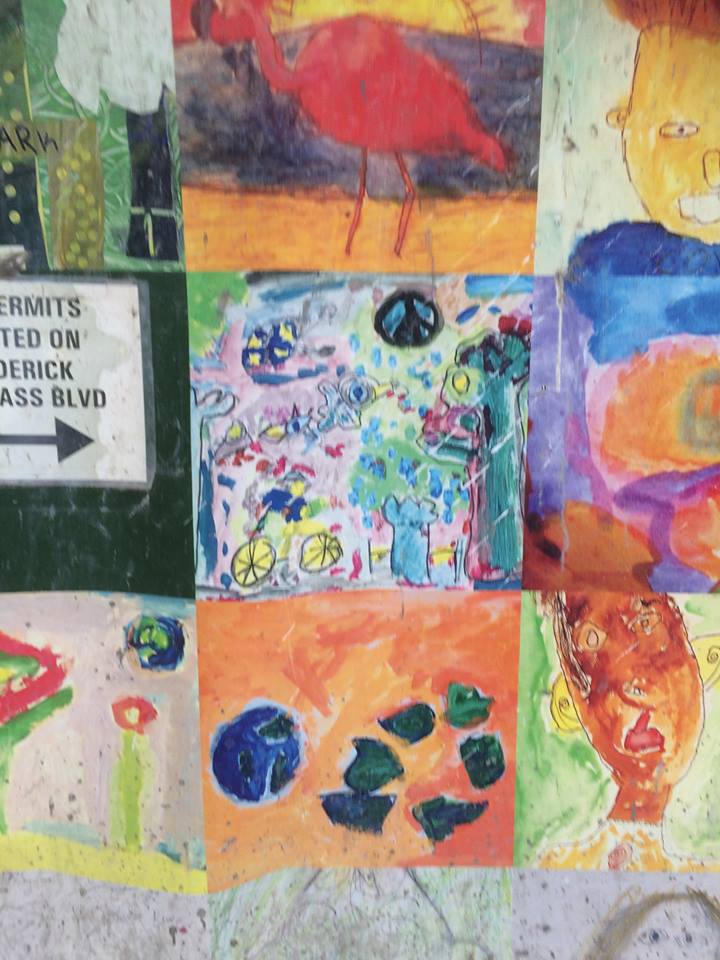

By third grade, he was struggling to read, but still learned content. He studied Kenya at school, and we bought a children’s book about Wangari Maathai. We discussed the Greenbelt Movement. Later in the year, his class was invited to enter an art contest for an environmentally-conscious real estate developer. The kids could draw a self-portrait or use art to answer “What does green mean to me?”

Clearly, my son isn’t a great artist, but with his background knowledge and comprehension, he still delivered the message with his prize-winning piece.

Had I read Natalie Wexler’s recent Atlantic article, I might have been led astray. While Natalie and most true literacy experts know about the importance of phonemic awareness and phonics, the Atlantic did not include that point in the article. Reading this article alone, I might have doubled down on vocabulary and experiential learning to build even more background knowledge. I might have missed the key skills he was missing. My son would probably still be illiterate.

It's important that all Atlantic readers advocate for great content, leading to increased vocabulary, background knowledge and systematic phonics at their schools. Wexler’s recent piece seemingly ignores the science of reading entirely, and a related piece she wrote last year gives at best a passing nod to the importance of systematic phonics instruction. There, she says, “One component of reading is, like math, primarily a set of skills: the part that involves decoding, or making connections between sounds and the letters that represent them.”

This is exactly the component my son was missing, and many other children are still being denied. [pullquote]My son was diagnosed with dyslexia with a particular weakness in decoding and encoding. Vocabulary, background knowledge and comprehension were not his problems. Phonics was.[/pullquote]

Although his school tried valiantly to teach him with a balanced literacy approach, it wasn’t until we switched him to a school that specializes in dyslexia that he began to read.

I began to read then too.

I learned about the five pillars of literacy. I learned about phonemic awareness, phonological awareness/alphabetical principles of English, vocabulary, fluency and comprehension.

I now understand that the “phonics lite” versions of balanced literacy are not well balanced at all. I learned that there is a huge disconnect at universities between the science of reading and the teaching of reading. I also learned due to a lack of teacher preparation, there is a clear dyslexia-to-prison pipeline.

Wexler isn’t wrong to point to building background knowledge as a critical aspect of comprehension that is often overlooked in schools. But she gave readers, including parents, an incomplete picture of the problems in schools and universities regarding the teaching of reading. Parents and the public need to know the whole story.

Debbie Meyer is a founding member of the Dyslexia (Plus) in Public Schools Task Force, a small group of community leaders working to help students with dyslexia and related language-based disabilities thrive in their neighborhood schools. She also serves as a board member of both the Dyslexia Alliance for Black Children and Harlem Women Strong, and is a member of the Arise Coalition Literacy Committee. Most recently, she was appointed as a contributor to NYC Mayor Eric Adams Transition Team. In 2018, she was named as an A’leila Bundles Community Scholar at Columbia University to look at the intersection of dyslexia and mass incarceration and the role of universities in changing the trajectory of struggling readers. Debbie’s lengthy professional career is in nonprofit management and fundraising. She lives in Central Harlem with her [dyslexic] husband and son.

The story you tell yourself about your own math ability tends to become true. This isn’t some Oprah aphorism about attracting what you want from the universe. Well, I guess it kind of is, but...

If you have a child with disabilities, you’re not alone: According to the latest data, over 7 million American schoolchildren — 14% of all students ages 3-21 — are classified as eligible for special...

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

Your donations support the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.

Leave a Comment