Feb 2, 2023 9:00:00 AM

by Lane Wright

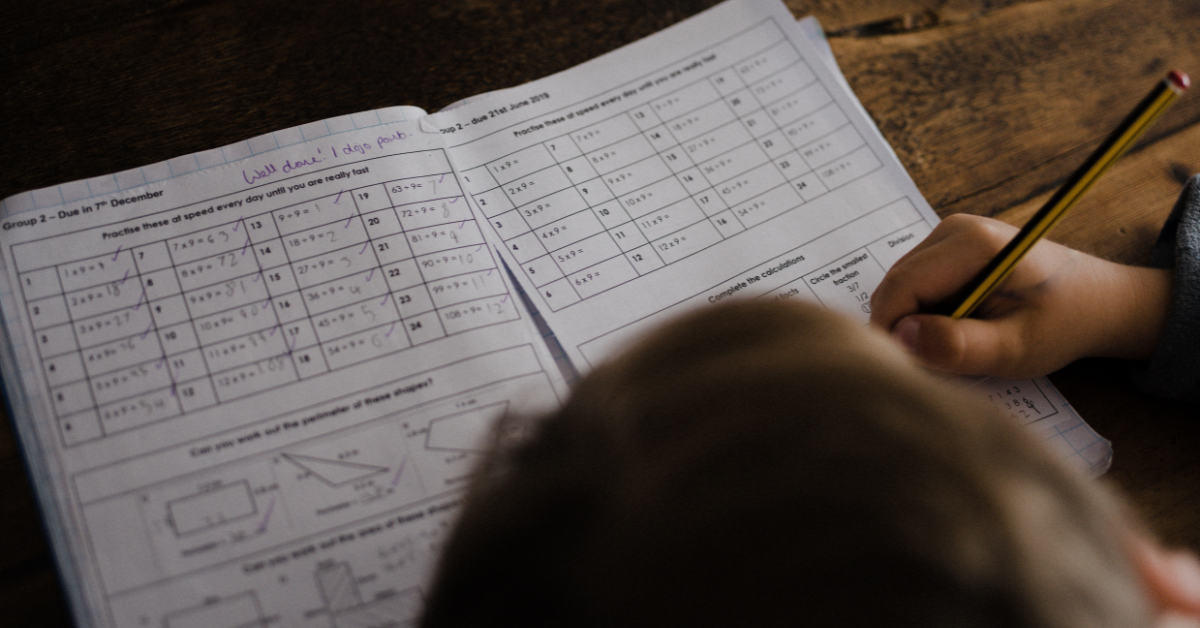

You may laugh, but I’m not afraid to admit I’ve been stumped by my third grader’s math homework. (Perhaps parents whose kids did Common Core can relate).

This was almost a year ago, so forgive me for forgetting the specific problem.

What I do remember is he was struggling and feeling somewhat defeated by it. This was one of those situations where we could have just followed the algorithm and produced the answer, but I really wanted my son to understand why it worked. Unfortunately, I didn’t even know why it worked.

I encouraged him to not give up. But I knew that encouraging words would be in vain if I didn’t give him some kind of tools for working through the struggle. Having no particularly bright ideas at the moment and only a deep desire to build up his confidence, I simply decided I would join him in the struggle.

We found a quiet place to work, away from his three non-stop-noise-making siblings and tried to figure it out. We reviewed a couple problems he had missed on a returned practice test, looked at the corrected answers and tried to rework them. When we ran out of space in the margins, we each took a clean sheet of paper from the printer and kept going. We created similar math problems of our own to practice and we worked side-by-side leaning over to share an idea or an attempt. We wore down the erasers on our pencils, but eventually we had a breakthrough.

I figured out the logic behind the problem and turned my attention to helping him see it too. But I was careful not to do it for him. I didn’t want to rob him of the aha! moment that I just experienced.

So I began asking him questions that would help him think the problem through. I let him struggle a bit more. Within a few more minutes he had his moment.

It was genuinely exciting. We high-fived. We did a few more of our made-up problems to drive it home and then called it a night.

That experience stuck with me. Not only was it just a sweet moment of triumph that my son and I got to share, but I got to see first-hand how important it is to let students struggle with math (or any subject for that matter!).

We’ve probably all seen kids, faced with a difficult math problem, decide they’re just “not a math person.” Maybe you were that kid once too!

As parents, teachers or mentors of children, we need to do a better job of helping kids know that it’s not only okay to get stuck, but that’s part of the deal. To struggle is to learn. In fact, some of the best mathematicians, such as Ben Orlin, Courtney Gibbons and others, became great precisely because of their ability to get comfortable with getting stuck.

A little over a year ago, I attended an education conference put on by ExcelinEd where Jo Boaler, a Stanford math education professor, explained how learning something new literally changes our brains. Learning forms new neurological pathways, or connects or strengthens existing ones.

The “very best time for your brain” is when it is struggling, Boaler says. “When you are finding something difficult, that’s when your brains are on fire with connectivity and growth.”

Unfortunately, she continued, “U.S. teachers have been trained to jump in and save kids from the struggle.” TNTP’s The Opportunity Myth (2018) reinforced that idea by finding evidence that “most students lack the opportunity to regularly tackle grade-appropriate assignments.”

Our students need the struggle.

But, it’s not enough to just tell students to be okay with getting stuck. Perhaps you can show them the steps of struggle. Let them know it’s fine if they’re not at the top step at the moment, but beware not to stay at the bottom step for too long.

Another popular analogy that might help students is “The Pit.”

This was shared in Boaler’s presentation, but you could probably have some fun drawing your own with your student. Both of these were developed by Jennifer Schaefer, a fifth-grade teacher in Canada.

Other tools might include making the problem more visual and drawing out the pieces. Or perhaps they could find objects that help them engage with the problem tangibly. The important thing is that students have time to deal with the problem. The more we can guide students through their learning challenges, the more they’ll get to experience true learning and the joy that comes from it, not to mention improved academic performance.

Lane Wright is Director of Communications and Advocacy for the National Council on Teacher Quality, and formerly served as Director of Strategic Growth for Education Post and brightbeam. Lane has more than 18 years of experience in strategic communications and education advocacy. He tells stories that help families understand how their schools are doing, how to make them better, and how policy plays a role.

Few issues in education spark more tension and debate than standardized testing. Are they a tool for equity or a burden on students? A necessary check on school systems or a flawed measure of...

Charter schools are public schools with a purpose. Operating independently from traditional school districts, they're tuition-free, open to all students, and publicly funded—but with more flexibility...

Despite the benefits of a diverse teaching force, prospective teachers of color fall out of our leaky preparation pipeline at every stage: preparation, hiring, induction, and retention. Here’s what...

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020-2025 brightbeam. All rights reserved.

Leave a Comment