Written by Tracy Dell’Angela | Aug 31, 2016 4:00:00 AM

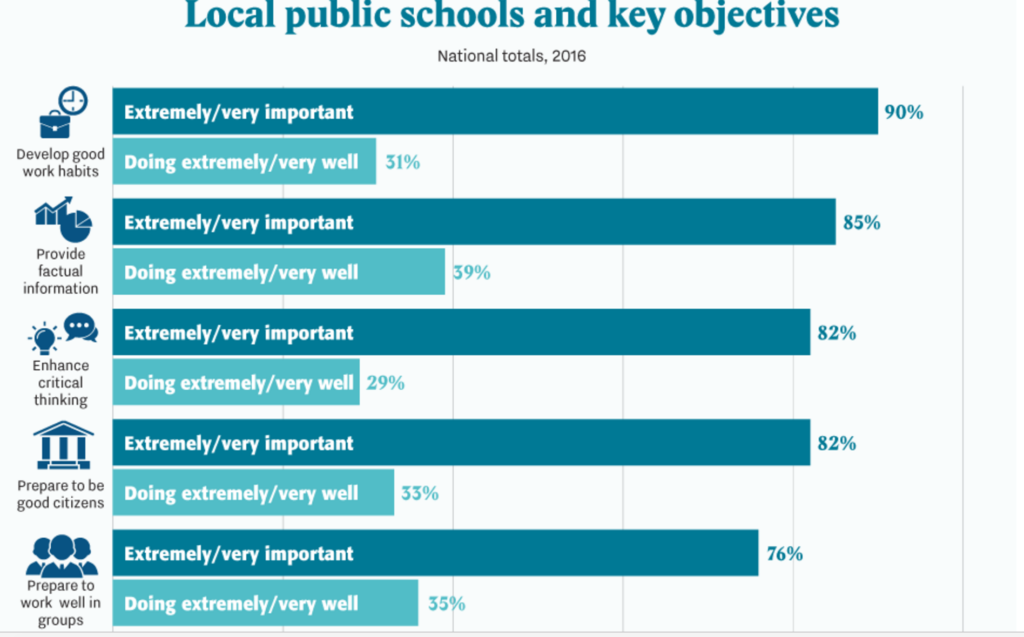

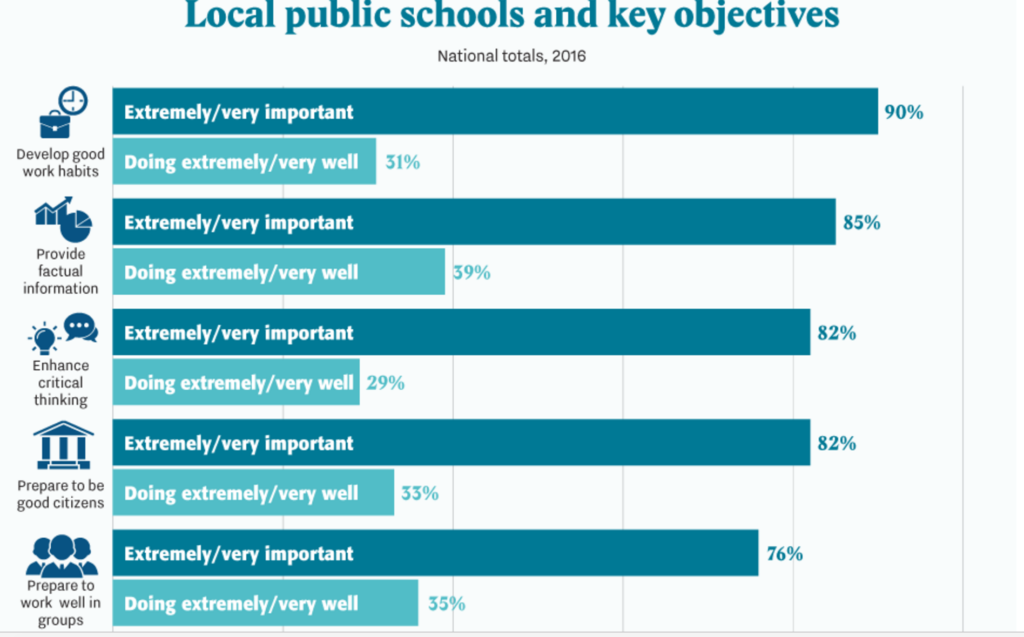

Opt-Out. Testing. Charters. Common Core. Closings. Accountability. Standards. Teacher Tenure. Teacher Pay. School Spending. If you’re in the education bubble, like we are, you spend the whole year thinking about these issues. But if you’re not, this is the time when a handful of organizations tell the rest of America what parents, teachers and other members of the general public think about these issues and value about their schools. The national polls then inspire an army of in-the-bubble pundits to try to make sense of it all. Today it was the Phi Delta Kappa International poll, which has been critiqued for the leading way in which certain reform questions are worded and interpreted. Two weeks ago, it was EdNext, which this year offered some rich insight into the education polling trends we’ve seen over the past decade. Much has been written about the key findings from each of these, but before I look at the similarities across both polls and what it means, I wanted to dig deeper at the issue of academic expectations—an issue that affects all schools, notably the ones that have been largely untouched by controversial reform initiatives such as school closings or charters. I’m always struck by parents who are quick to give top grades to their local schools, but when you look close, these parents aren’t particularly enthusiastic about what their students are learning and the value they are getting for their dollars. Consider this set of questions in the PDK poll:

White parents are 17 points more likely than nonwhites to think their child feels too much pressure (31% to 14%), but they’re less apt to feel that they’re the cause of it (30% vs. 49%). Instead, they’re 17 points more likely to attribute the pressure to their child’s teachers (26% to 9%).Not surprising at all, but still illuminating: Worrying about too much academic pressure is a luxury rarely afforded to non-White parents, who instead have to worry that their schools and teachers are underperforming and expecting too little from their children. Looking across the two polls, there are some common themes:

- A solid majority of Americans don’t support the opt-out movement. Both polls show that respondents oppose letting parents opt out of state tests—70 percent in EdNext poll, and 59 percent in the PDK. The strongest pushback was from Black Americans, hardly a shocker given the general composition of the opt-out movement—White, affluent and largely suburban.

- Grade inflation is alive and well, when it comes to how Americans view their local schools compared to schools across the nation. About half of respondents in both polls—48 percent in the PDK poll and 55 percent in EdNext—give their local schools a grade of A or B. Parents have the rosiest view—70 percent would give their child’s school an A or B. This plummets to only a fourth of people nationwide (in both polls) who would give the nation’s schools top grades of A or B.

- People want high, uniform standards in their schools. Period. They just don’t want them to be called Common Core. The EdNext poll focused more on the uniformity question, with two-thirds supporting “standards for reading and math that are the same across states.” For PDK, the findings are more mixed, but a plurality of parents (47 percent) say new standards have increased how much their child is challenged academically, with 31 percent saying it’s had no effect.

An original version of this post appeared on Head in the Sand.

Photo courtesy of PDK International.